Following the announcement last week that the Aspen Chamber Resort Associated has decided to drop its membership with the U.S. Chamber over its position on climate change, the following blog has been submitted to tell the behind-the-scenes story of the effort that went into this huge victory:

Following the announcement last week that the Aspen Chamber Resort Associated has decided to drop its membership with the U.S. Chamber over its position on climate change, the following blog has been submitted to tell the behind-the-scenes story of the effort that went into this huge victory:

“You’re thistle in the garden patch…” an Aspen rancher used to tell his daughter. “And you’ll outlast ‘em all.”

Through similar prickly technique, another domino in the US Chamber battle fell on Tuesday when the Aspen Chamber Resort Association announced that it would end membership in the US Chamber because its “archaic” stance on climate policy didn’t dovetail with the goals of a ski town.

Many towns and businesses have dropped the Chamber over the last few years, and from the outside, it looks like these moves just happen. But of course that not true—even thistle fights an uphill battle.

In the case of Aspen, the decision took more than two years, and was the product of multiple prongs of attack—some respectful and well intentioned; some aggressive and misguided. It involved civil discussion, outrage, fury, fights played out in the newspaper and in board rooms. The effort caused some participants—on both sides of the issue—to age in dog years, and others many sleepless nights and blood pressure episodes.

A letter writing campaign at the national level, which blossomed through the action of multiple nonprofits, brought the issue onto the community’s radar, and probably helped push the local papers to editorialize about the topic. But it also mostly pissed off generally sympathetic local chamber board members who didn’t want to be told what to do by outsiders from Portland and Boston.

In the end, what worked best was what you might call “Aspen casual.” Eyeball to eyeball conversations among constituents—supporters and opponents, board members and elected official, that started with a request for a personal meeting—not a phone call or an email exchange or a letter to the paper—and began with an open question, and the patience to listen: “Tell me what you make of this thing.” It required swallowing one’s righteousness and trying to inhabit the opposition’s mindset. The primary obstacle early on, as is often the case, is what I call the supermarket problem: given a choice between an action that might help save the world, or facing the awkward social consequences of that decision (a nasty encounter with an opponent in the cereal aisle in the supermarket) most humans will choose to avoid that encounter, despite the asymmetry of the choices.

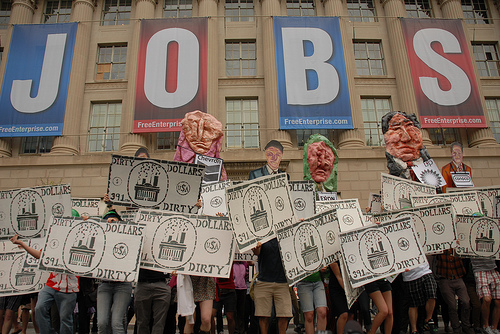

After all the work, it would be nice to proclaim a great victory, and one is inclined to do so. Aspen, after all, is an iconic ski town, a press magnet, and host to hugely influential visitors and residents. It’s entirely possible Aspen can create a domino effect among winter sports communities, and that coverage of the resignation will be both durable and influential. But it’s also possible, even likely, that Aspen is just a gnat to the U.S. Chamber, which is mostly funded by a few big corporations and unapologetically opposed to real action on climate. They likely feel well rid of this pest. The vast machinery of monied politics crushes forward regardless of what silly little Aspen thinks.

The seemingly unstoppable onslaught of climate change and what we’ve done to our democracy, our climate, and our humanity often makes me wonder what we have become as citizens, parents, and human beings. It gives me the discomfiting sense that we may have lost touch with the things we care about most: our children, and our neighbors. As a part of this group, in slack moments of many days I feel that, to quote Bob Dylan, “I can’t hear the echo of my footsteps, or remember the sound of my own name.”

But what the human interaction and intestinal fortitude required by our local campaign taught us—taught me—was more valuable, perhaps, than what it told the U.S. Chamber. It required that we check our passions to allow a conversation. It forced human engagement.

All of us involved in this effort know that 350 is a targeted concentration of molecules in the atmosphere that will require us to control our outputs and reveal our gameness. But 350 is also part of us, bodily. It is both numinous and numerological, a number linked to the birth of our multi-decadal “generation climate.” More than atmospheric chemistry, 350 signifies an act of restraining, and unleashing, something within ourselves.

-Auden Schendler is the Vice President of Sustainability at Aspen Skiing Company and is author of Getting Green Done.